Licking War Wounds

August 24, 2022

Andrii Dostliev & Lia Dostlieva

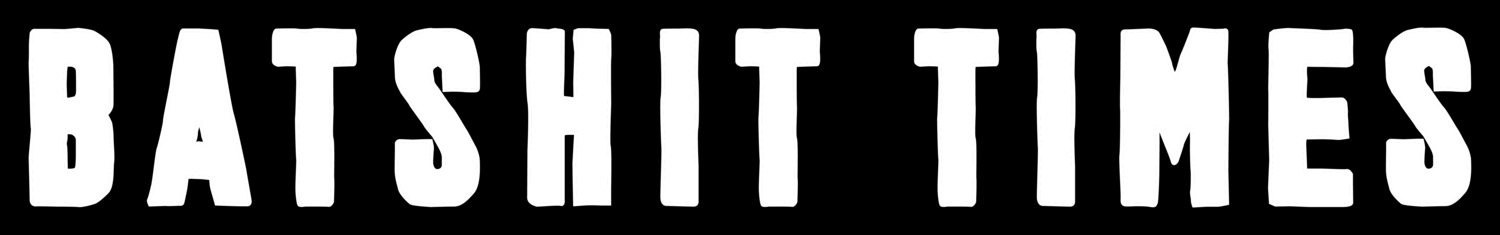

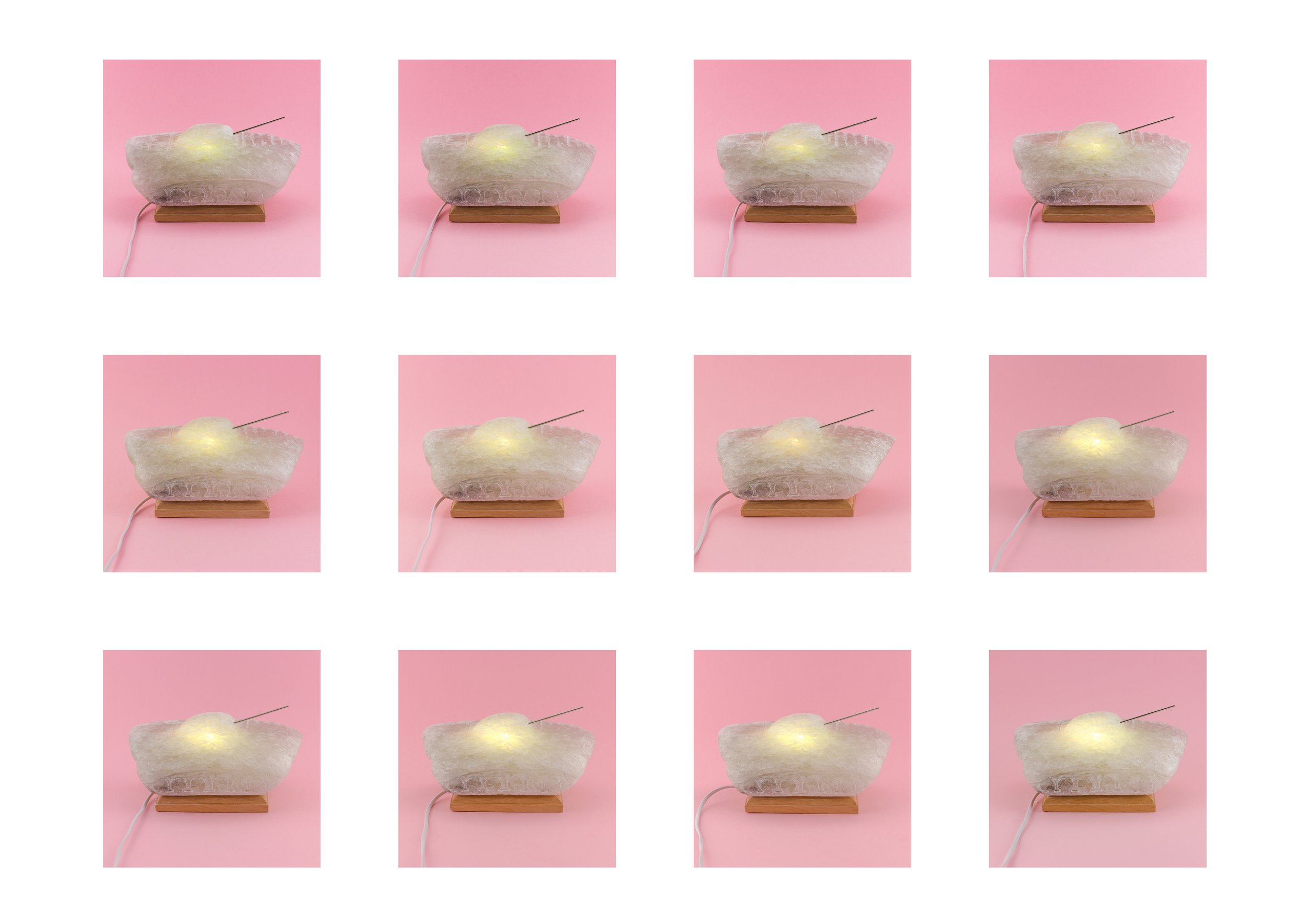

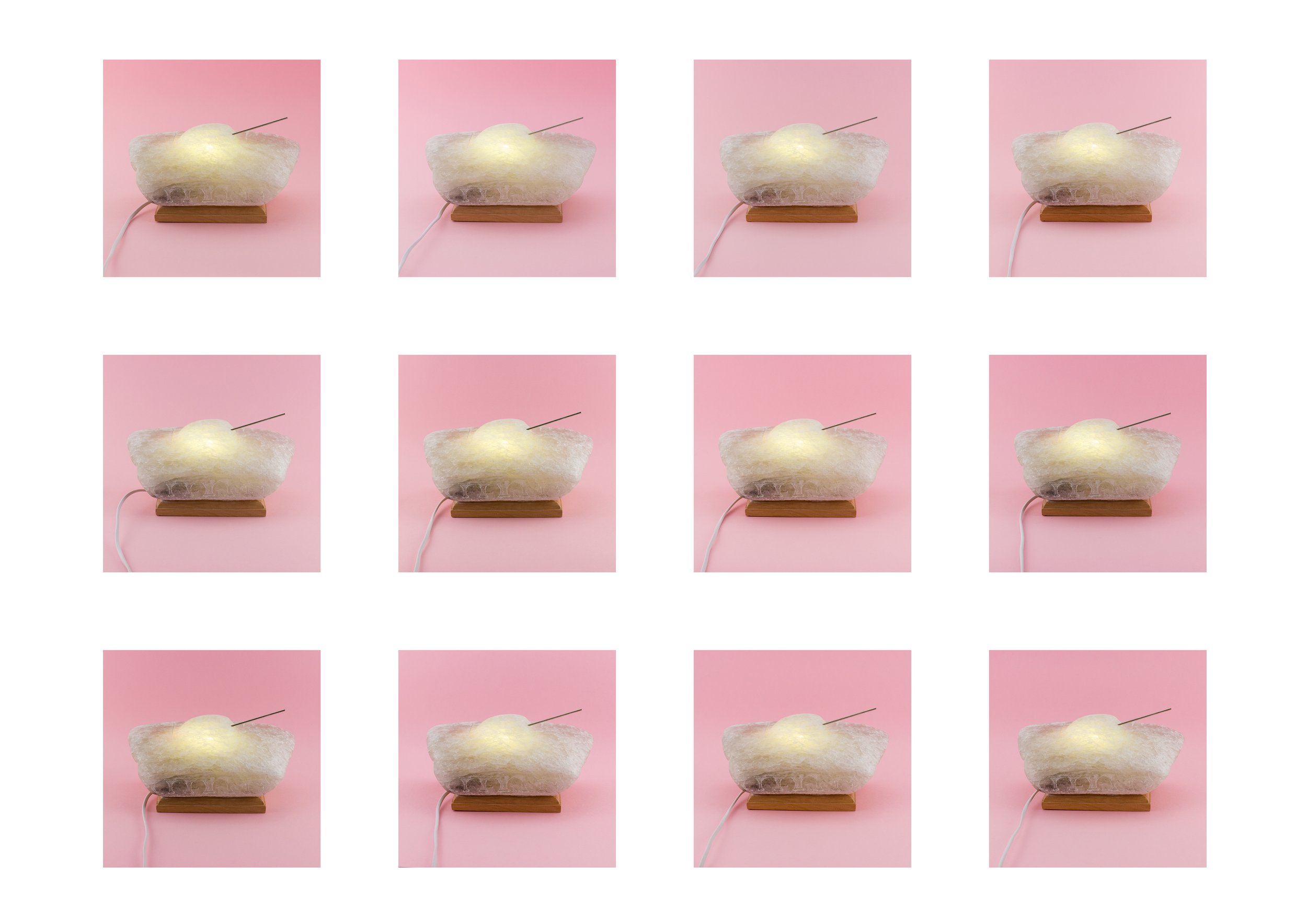

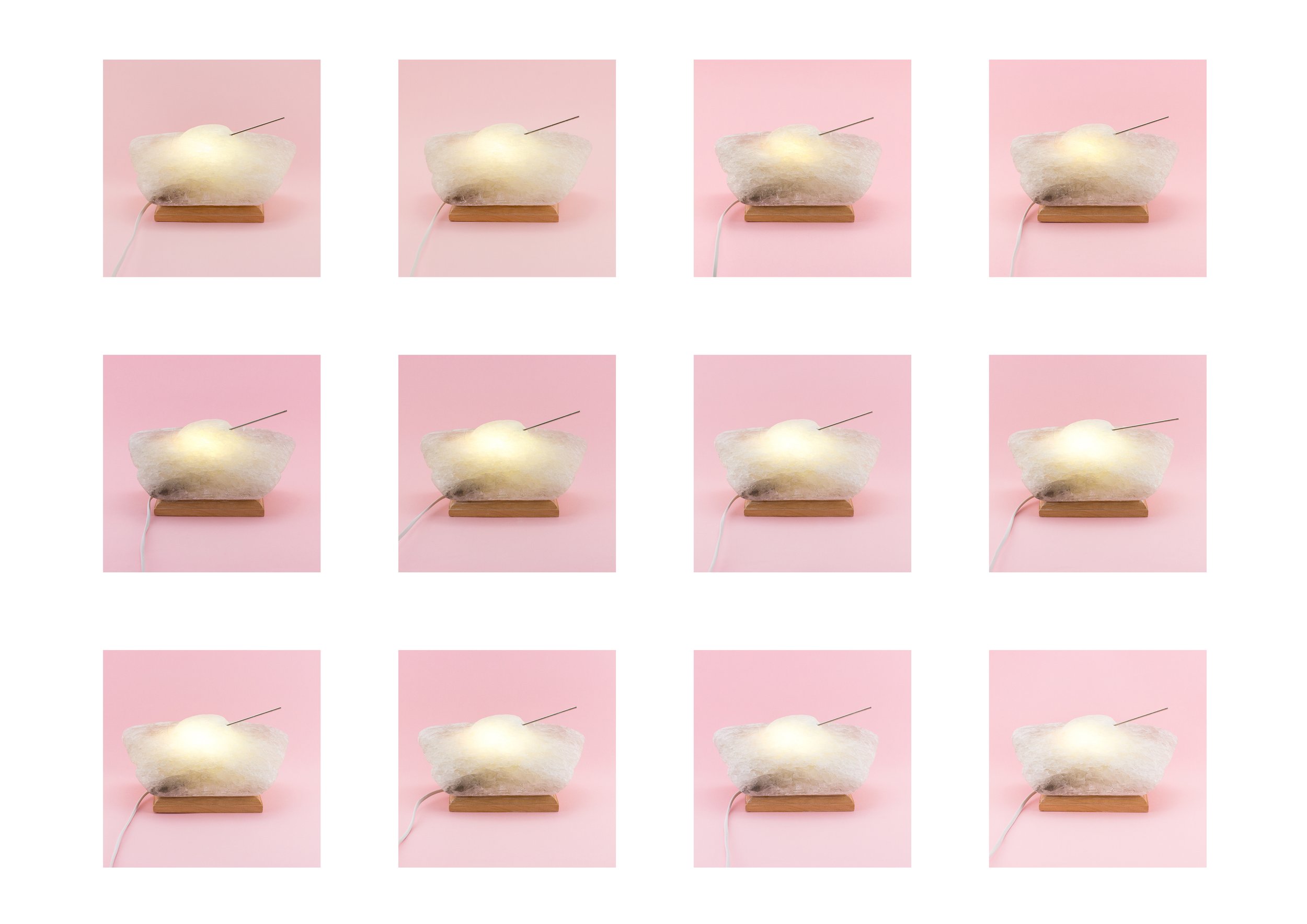

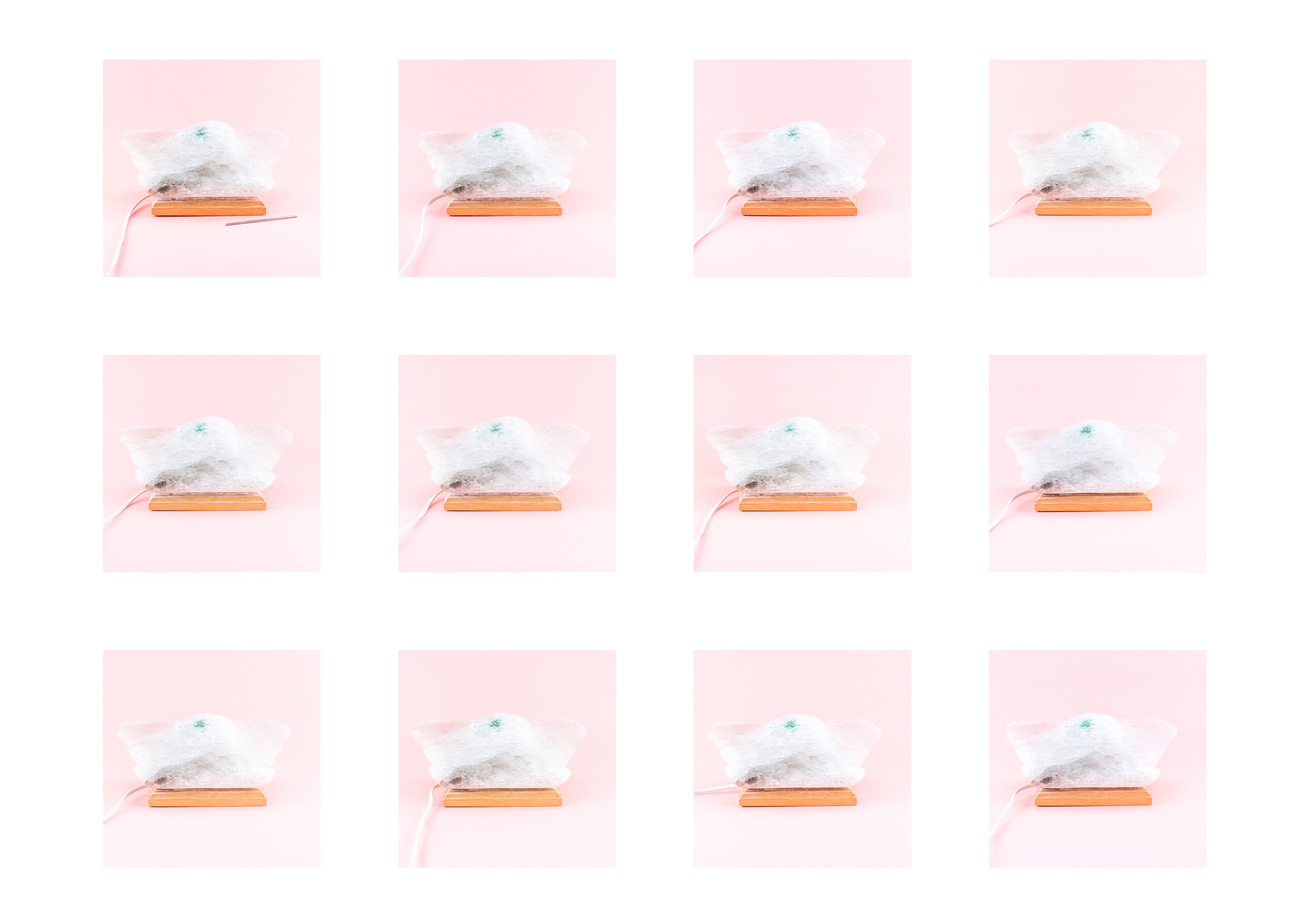

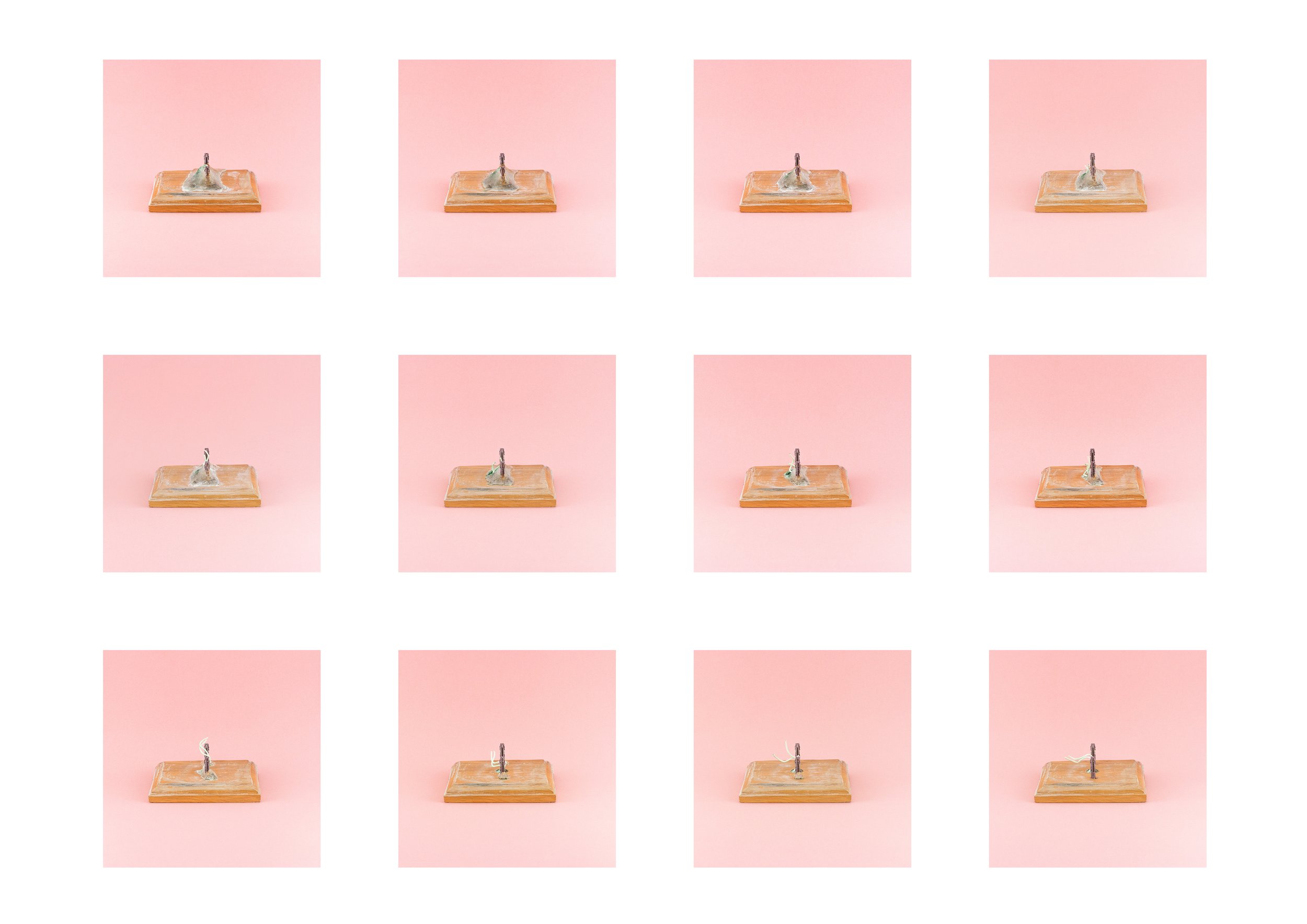

“This tank-shaped salt lamp was purchased from a souvenir shop in Bakhmut in late 2016. Bakhmut (formerly Artemivsk) is a city in Eastern Ukraine famous for its salt mines. For a short period of time in 2014, the city was under occupation by Russian terrorists from the so-called DPR. Various salt lamps were always a large part of the city’s souvenir industry, but this particular kind, in the shape of a tank, only appeared after the city was liberated by the Ukrainian army.

Such tank-shaped souvenirs are only a minor aspect of general traumatisation of the Ukrainian society caused by the war lasting since 2014. This traumatisation is yet to be overcome by the Ukrainians, a very long and complex process that might take many years. One of the many war wounds that we have yet to lick.

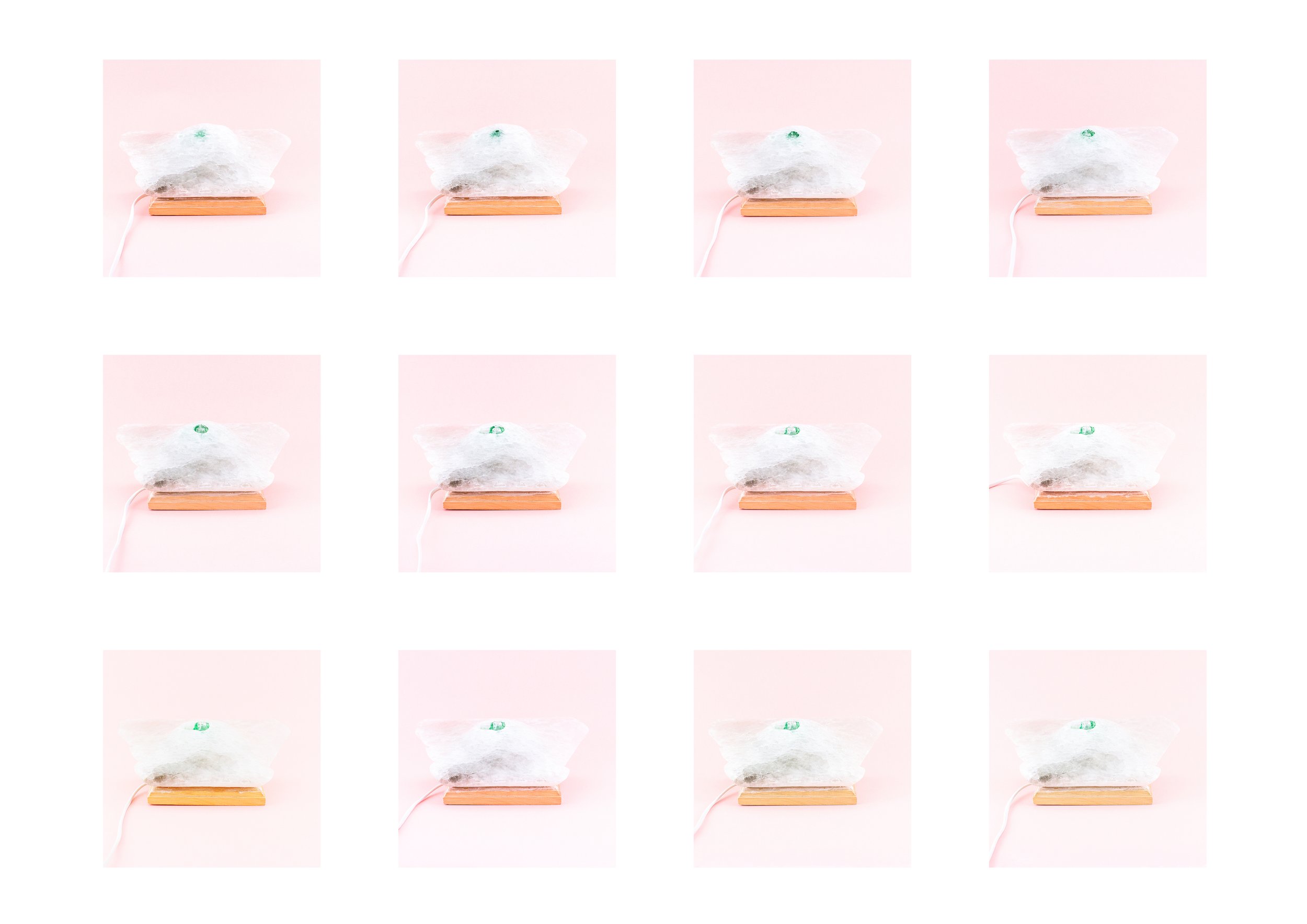

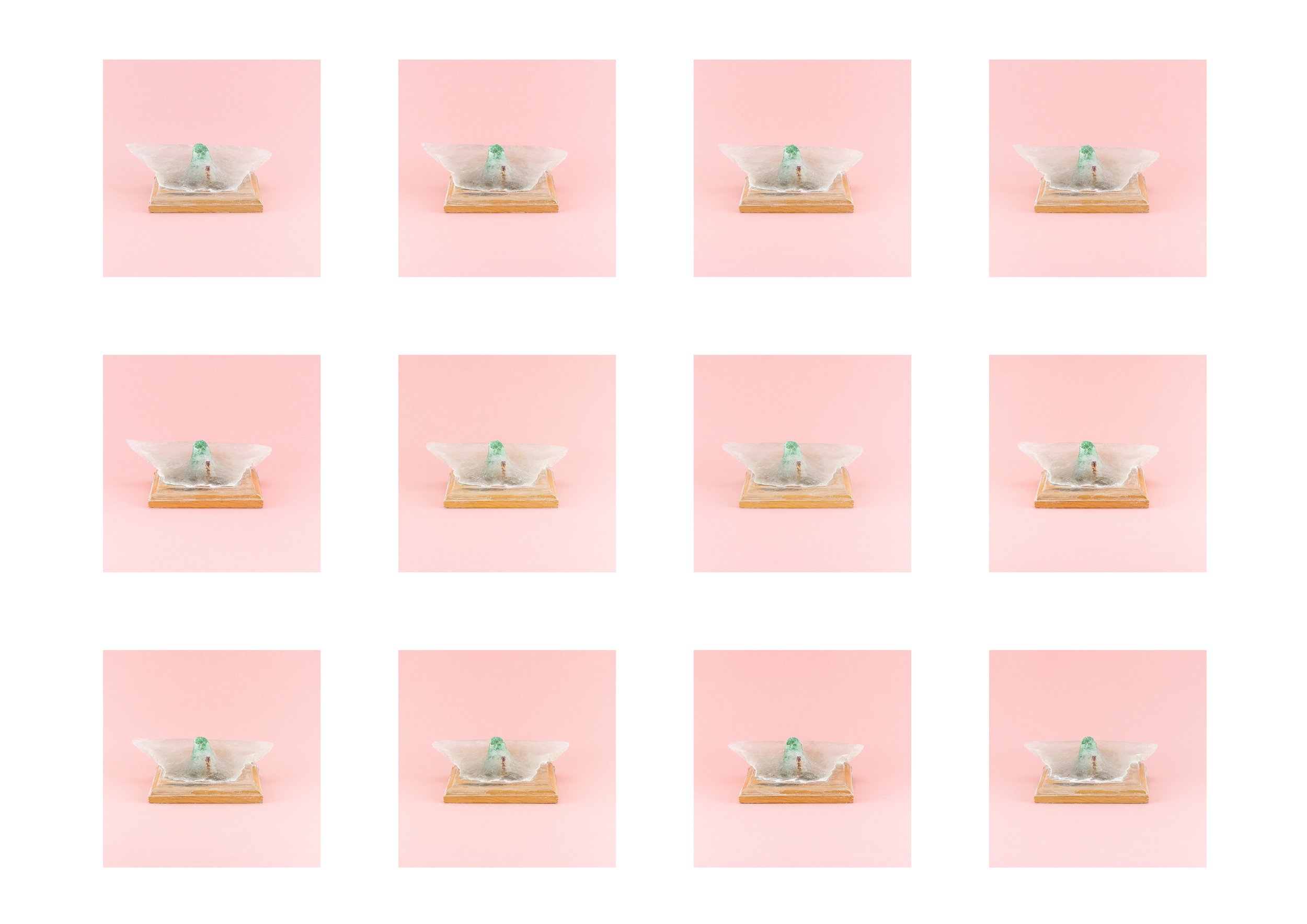

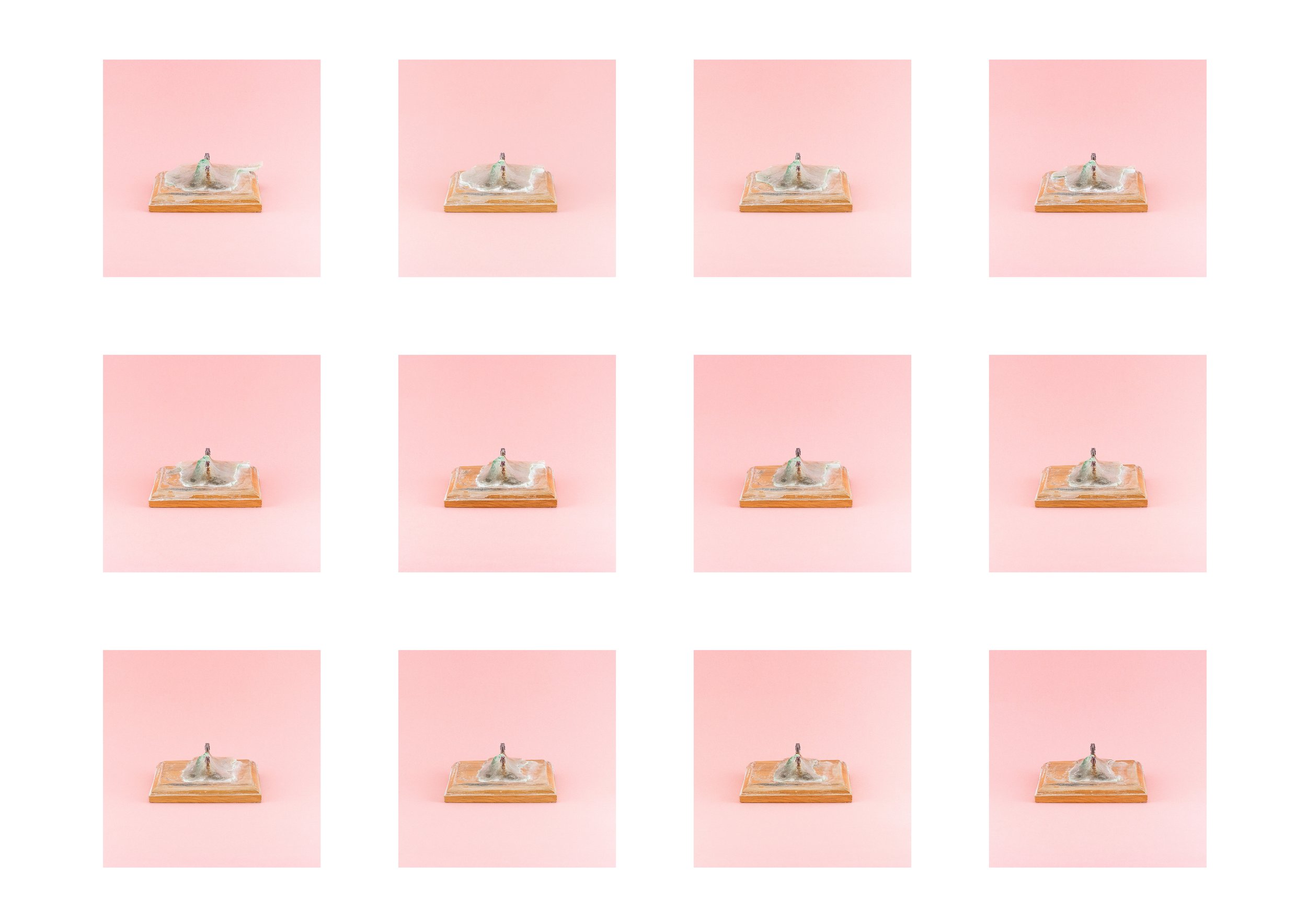

And we were literally licking (yes, physically licking this salt tank with our tongues) day by day, bit by bit. This slow and quite painful process demonstrates the slow and not necessarily successful re-shaping of the object of trauma.”

The two artists completed this long-term performance in 2021 after five years.

This interview took place on January 4, 2022, thirty days before Russia once again invaded Ukraine.

What is the origin of Licking War Wounds?

Andrii Dostliev:

It was almost by accident that we stumbled upon this salt lamp. Our friend, a journalist, was traveling near the front line in the city of Bakhmut, which is the center of salt mining in Eastern Ukraine. A main tourist attraction to the Soledar salt mine in that city are souvenir shops that sell salt lamps, these moulds of cats and shapeless forms. They were always nice, normal shapes of things. When the war passed through the city, which was an occupation that lasted several months before the Ukrainian Army liberated them, these souvenir shops started to sell salt lamps in the form of military machines. I thought this was an excellent symbol of how people were touched by the war, so I asked him to buy one for me.

On one hand, these objects are aesthetic symbols of war trauma and war wounds. But on the other hand, their material composition adds layers to their meaning because they can be built up and broken down. When you give an animal a brick of salt, they’ll lick it. So we decided that we would do the same with this lamp and lick it until it was fully gone.

Lia Dostlieva:

Based on pictures our friend sent us, we didn’t realize the size of the lamp. We thought it’d be much smaller and would only take about 6 months to lick it away, but it was much bigger and pretty heavy, about 2 kg or so. It was too late to turn back because we had already embraced the idea, and so we began. The intention of photographing it over time was to show its disappearance. The rate of change is more apparent in earlier photos compared to later ones. Overall, the project took us five years.

You now live and work in Poland. How was licking this salt lamp a form of working through the trauma of the war?

Lia Dostlieva:

There was a saying amongst our friends that once our project was complete and the salt was completely rubbed away, the war would end. Many people really believed this. But when we finally finished licking, nothing happened. We were forced to question, what is still going on?

I think I was disappointed when we ended because of this hopefulness we carried throughout. The project had developed this magic. When we finally exhibited the photos in one place, it felt like a documentation of a failure in a way. We realized we had no impact on reality and no clue what the future holds for Ukraine. Just no idea.

Thinking of the body horror of this project, were there moments when you were disgusted by the salt and your body completely rejected the act of licking?

Andrii Dostliev:

For me, it was never disgusting because of the war symbol, but for the salt.

Lia Dostlieva:

It’s really unpleasant to lick salt over several years.

Andrii Dostliev:

It’s formed of crystals, so every now and then we’d cut our tongues and bleed on the salt piece. But we tried not to bring that element into the piece.

Why did you choose the pink backdrop?

Lia Dostlieva:

In my earlier projects about Donbass, I started to integrate pink because it’s a beautiful color, but it’s also very close to red, which is the color of blood. The relationship is there somewhere, but not directly. So we liked the idea of using pink as a backdrop for the tank, a symbol of war.

Speaking of your earlier works, you have many projects exploring these conceptual issues of trauma and violence across imaginaries, but you depict them with a lighthearted tenderness. Where does this strategy come from?

Andrii Dostliev:

It started after the war. Before, we were working with photography and book crafts. That changed when I began a project on my own family archive, which is left in Donetsk and is inaccessible to me now. I decided to reconstruct it with found photos from flea markets, and that led to thinking deeper on these topics and expanding from a Ukrainian context to wider Eastern European issues.

I’m interested in how commercial objects become art objects, which we explore in Licking War Wounds. Why would someone sell a tank-shaped salt lamp in a region affected by war? It reminds me of a similar project of mine, 2.Weltkrieg in Blumen (Natürlich ohne die Blumen im Bild). I stumbled upon a seller on eBay named route_67 who was selling photographic prints from WWI that depicted soldiers and military parades, etc. To protect the copyright of the image so that no one would steal them, the seller digitally enhanced every image with pink flowers that covered essential parts of the picture and placed them in such a way that cropping them out would prove impossible.

It struck me that they did this for purely commercial reasons. There was no aesthetic or conceptual thinking behind this. But what happens to the image is still interesting because it becomes even more pretty, in a way, despite being an archival image of war. Should it be pretty? Should we just look at these photos as merely archival images with flowers over them? Or are they artworks? But can they be artworks if they were never intended to be that way? This gap between the images and our gaze upon them was something that I wanted to talk about in this work.

Why do you think you’re drawn to archives in this way?

Andrii Dostliev:

I like to sift through archives and assemble my own small collections from larger bodies of images. Sometimes I see a minor connection to something peculiar or funny or interesting to me. I like finding things that are worth thinking about.

April 12, 2022:

“We finished this project and conceived the book version of it in what seems now like another era... when we rather naïvely believed that we could already estimate the scale of the war and carefully start speaking about its consequences. By February 24th, the book was ready to go to print. And then everything changed. All our work suddenly did not matter anymore.

And still, this project feels now like a relic from the past. Like one of those old Soviet monuments with tanks or APCs that Russian soldiers were now shooting at while they were occupying Ukrainian towns and villages.”

You can purchase the full 248 page book at www.89books.com