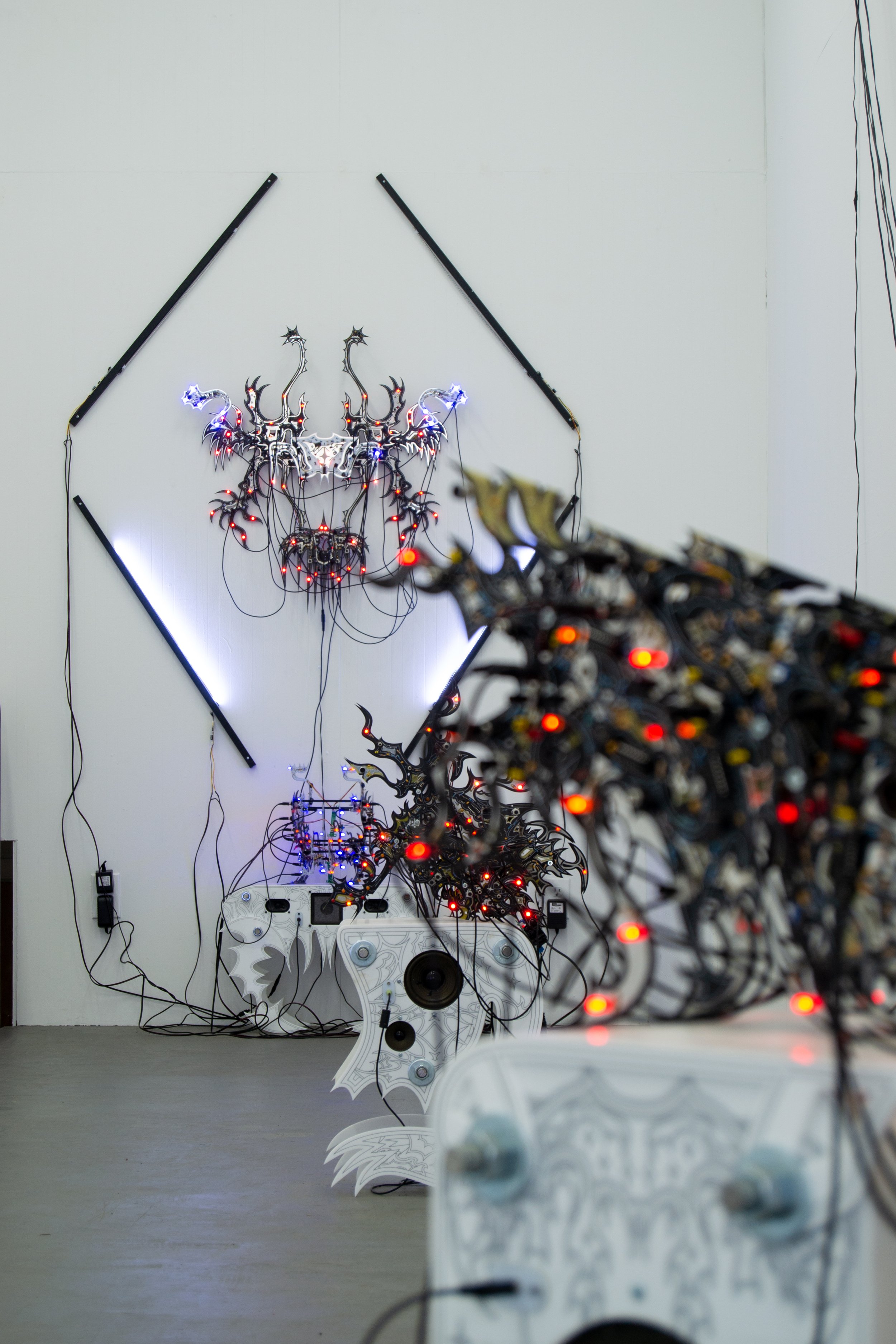

Cry of the Valkyries

June 29, 2022

Brian Oakes

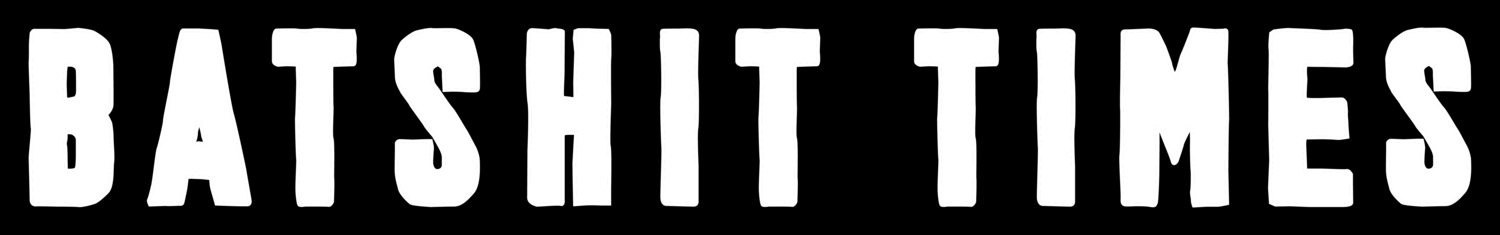

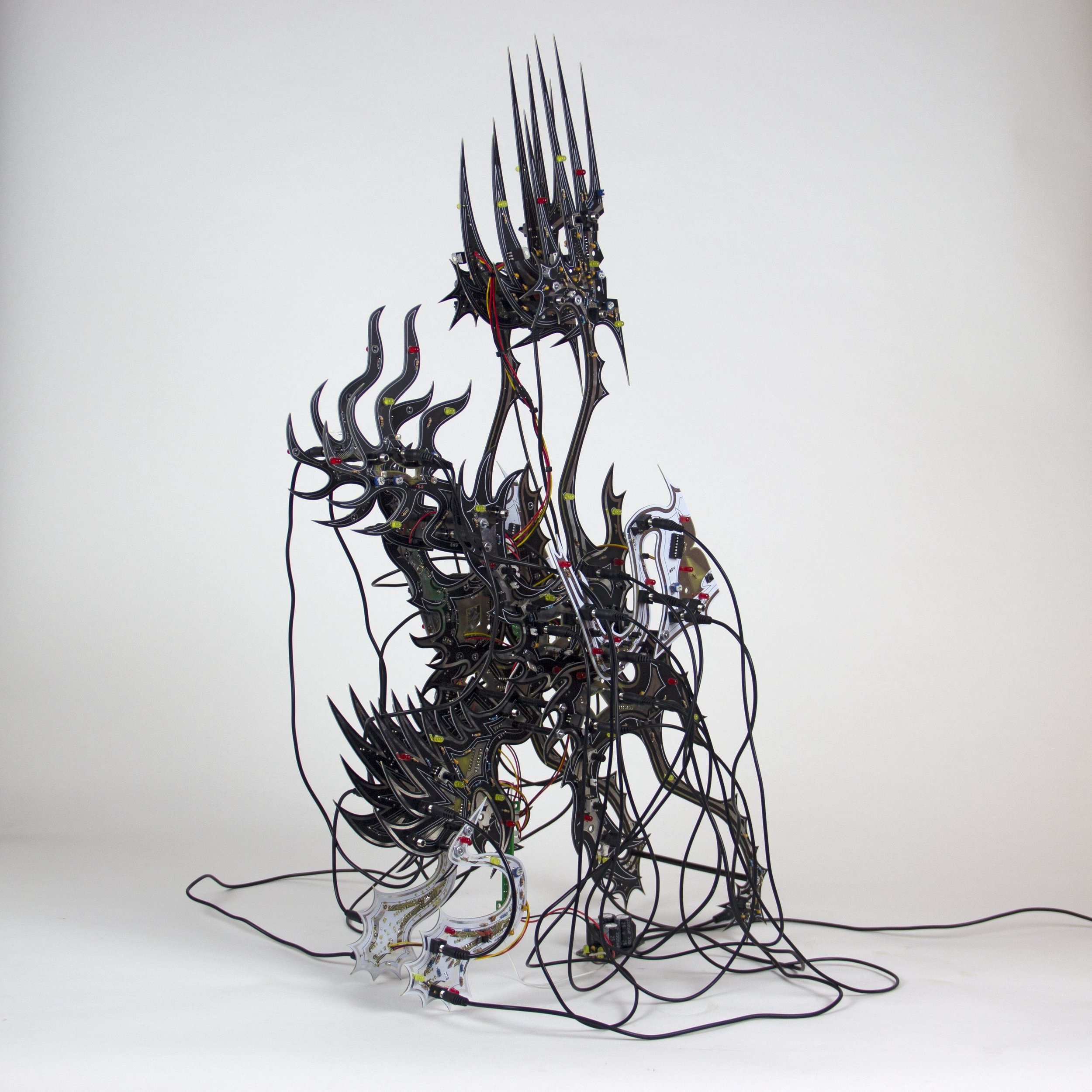

Brian Oakes’ printed circuit board (PCB) sound sculptures could either be the last thing you see before you die, or the angels that greet you in the afterlife. Their songs of praise are not hymns, but ambient drone progressions and feedback loops sampled from the environments around them. Anticipating your footsteps and the whispers on your breath, these sculptures mimic the viewer in unexpected delay, generating trance-like soundscapes. Chandeliers, wall hangings, and upright behemoths work in concert to communicate the viewer’s thoughts back to them, all as circuit lights twinkle on and off like an abandoned carnival ride.

Making sound-producing circuit board sculptures is a fairly unique medium. How did you get into it?

It came about through experimentation. For my older works, I used two-by-fours to build grand sculpture spaces that people could sit inside of. At some point, I wanted to add an ephemeral aspect to the work, so I started building little sound-making machines that could also vibrate a viewer at the same frequency as the work. I was making all the circuits by hand then, but the process was finicky, and they would break a lot of the time. I felt my physical abilities limited my scale. After leaving school, I didn’t have access to the same facilities anymore, and I turned to printed circuit boards. I realized I could have them all connected and have something ten times more sophisticated than before.

At first, I was putting circuit boards into old pieces. But I realized that some boards looked better on their own and should be sculptures themselves. Some were flat, so I thought they should be framed. I built the language for what I’m doing here over time.

What’s your current process for getting these boards made, and how do you come up with these shapes here?

I work with this production company who have always been open to the weird shapes that I want to do. The ability to print circuit boards is more affordable and accessible than before. The only reason that these shapes I use can exist are the insanely high calibrated precision machines only found at a certain level of industry. Though, when I first started working with this place, I learned that the resolution I was working in was beyond the physical limits of these machines. My designs made them crash.

For the shapes themselves, I like to practice automatic drawing, the discipline where you draw without thought. After a while, I’ll meditate on and pump out a bunch of different forms. When I’ve landed somewhere, I’ll use Rhino, a computer graphics and CAD software, to build up a bank of shape drawings. I’ll match them and mix them and see what strings flow through them all. Then sometimes, I’ll take the resulting shape and start the process over, meditating on just that individual shape. I’m working on this Chandelier project right now, in part for a show I might have coming up in Kassel, Germany. I knew I wanted the pieces to have a radial pattern where the limbs would all stem out from the same center compared to some of my sculptures that I’ve constructed with parallel planes of boards. With that constraint in mind, I drew the first set, scanned them into the software, and experimented, round after round, until I landed on the sharp shapes you see in the final design.

I appreciate the question. When talking about anybody’s body of work, something that has become apparent to me is the unconscious and conscious separation. As an artist, when you practice your work and continue to build it, you build habits, progress, and get better. But the more known your practice becomes to you, the more it becomes an unconscious habit. And so it becomes even less known to you in that way. And it makes the task of describing a body of work like trying to describe your position on a moving escalator.

I make art because it’s compulsive. There’s nothing else I’d rather be doing than this.

I know you’ve worked with other materials in the past. How has your process as a sculpture artist evolved over time?

This is the first body of work where I know the material language going into a project. No matter what the sketch looks like, it will be a circuit board. That was never the case in my previous work. It was always capital “C”-concept, and then I would build out the best illustration to get there regardless of material. But here, I’ll sketch and sketch and sketch, and no matter what I draw, I’m going to imagine it as this building block in a laid-out context.

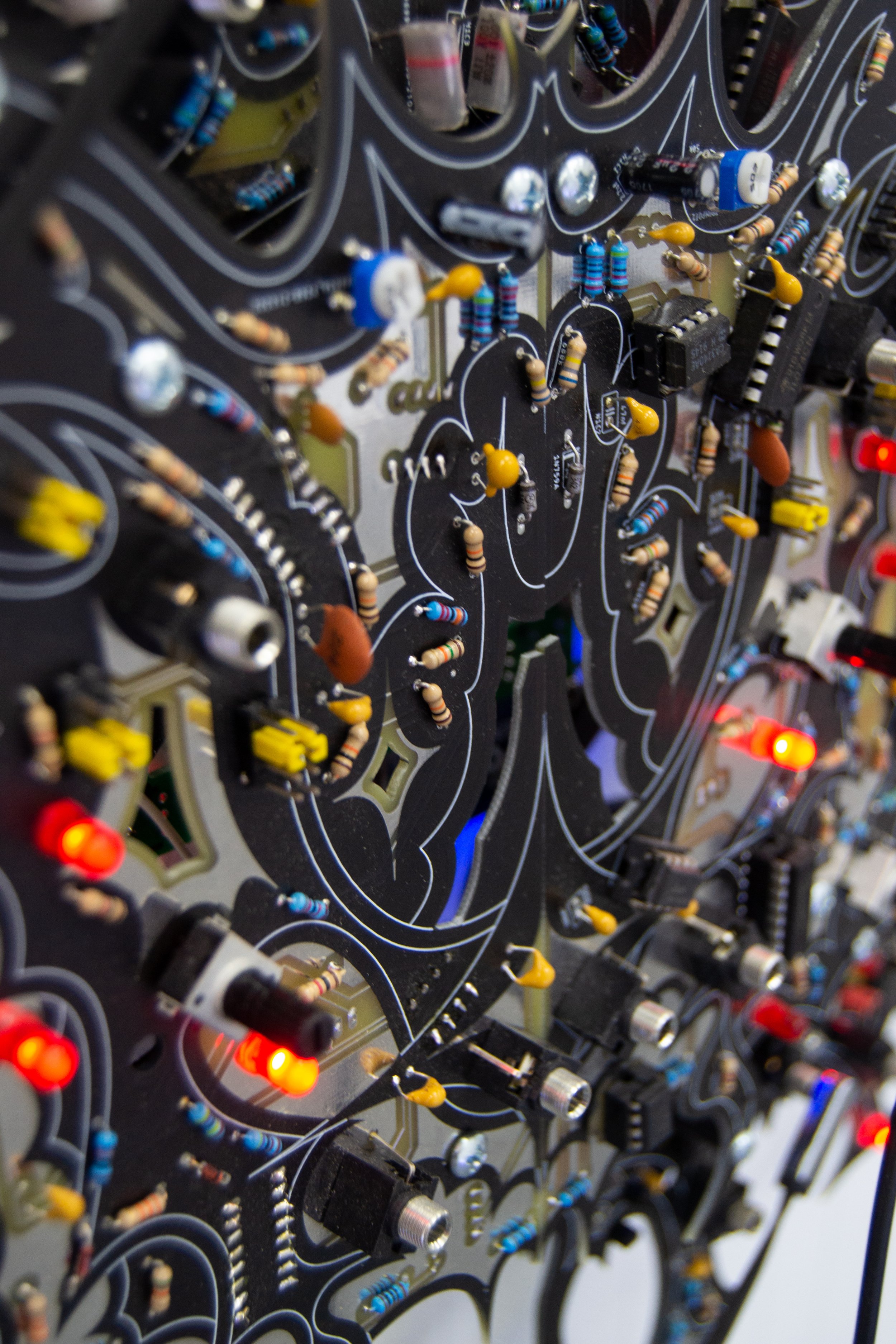

I’ve designed all these elements and circuits over time, and now I copy, paste, and reconfigure my way to a finished board. The whole process of sketching to ordering has typically taken about a month. But it’s faster now that I use many of the same circuits. I usually order the minimum amount of boards possible, test everything out, and then proceed with a bulk order if everything works. Now that I know some of the limits, making circuit boards is similar to creating a printmaking series. You get your connections and outlines down. You get a solder mask, which is the color that you see on the boards. And then you get a silkscreen that tells you where all the components go. There’s a lot of room for playing around here with inserting design, texture, and shape within that.

What’s your current process for getting these boards made, and how do you come up with these shapes here?

All my circuits are technically analog, actually. It keeps me from having to use an Arduino or something like that. I tend to bulk order pieces, and each piece is generally responsible for a hyperspecific function. Some components are delay modules or amplifiers, or they might grab and hold onto voltages. There’s no code or anything that tells these sculptures how to work. It’s all internalized function and self-dialogue.

I do code, but mostly as freelance work for other artists. That’s where I’ll work with Arduinos. I like working analog because analog is so tied to the material. I have a bunch of oscillators and small capacitors that create the tones that you hear. But if you were to a different type of capacitor with the same value, it would sound totally different. I love the relationship between material and output.

How did you go about learning the technical side of this medium?

On the one hand, I do just like building things and experimenting. But I’ve learned a lot from the online community that exists around electronics and circuit design. You can find learning materials on anything. Now, I’ve had the chance to do a few tutorials on the crazy shapes I make and run workshops about circuits I’ve designed. So it’s been nice to also contribute back to that community in small ways.

How big is the community of circuit board artists? Who are some folks in the medium that you admire?

There really are so few of us working with circuit boards. I admire any artists working with electronics in general. My studio mate, Emmett Palaima, is one example. I also really like Kelly Heaton’s work; she makes a ton of circuit board work. Max Hooper Schneider has been doing great and bizarre work with metallics. There are a ton of great electronics artists, both old-school and currently working like Peter Vogel and Peter Keene. I also admire Harry Gould Harvey IV and the artist collective ASMA based out of Mexico City.

I really love Birch Cooper and Brenna Murphy’ collective, MSHR. They do crazy performances, but they also build out these installations where it’s all these beautiful fractal patterns, with synthesizers and different colored lights embedded in them. People walking through the space affects the lighting, which affects the sound, which makes crazier sounds, and it just keeps sending feedback into itself from there. Their stuff is wonderful.

So what is the actual material here? Do you ever feel scared in your own studio that you’re going to topple something over? They seem like they might be fragile.

Most of the pieces are made of fiberglass, resins, and similar materials, so when I accidentally brush my hand over one, I’ll get cut before it breaks. I did have someone knock one of these over from a pedestal at one of the openings. I was right there, so I could catch it and put it back on. It was all fine. I mean, I don’t want to knock them over for sure. But they’re pretty sturdy.

I also make some out of foam and others out of medium-density fiberboard that I’ve layered together, routed, then sanded. The paints give them a different finish.

You have a range of sizes on these pieces. How big are you trying to go?

I feel the move has always been to see how big I can make them. The largest single board the production company can handle right now is 30 centimeters by 30 centimeters. To go bigger than that, I’d have to start making them myself—which I have done before. When I was still in school, I used a process where you draw the circuit schematic with a Sharpie, etch it, and then the Sharpie is the only thing that stays behind with the copper underneath. I realized that the result was a blank canvas. Back then, I had access to a Formlabs printer, which can print full-color UV images on any surface, so I would print images onto my circuit boards. Formlabs is the company that normalized that process, whereas MakerBot is the equivalent for the 3D printers that print with what is essentially a fancy hot glue gun.

Would you ever consider having a studio factory?

I don’t think so. I make art because it’s compulsive. There’s nothing else I’d rather be doing than this. But I’ve worked for many artists where that’s not the case. When it comes to all of the art you see in museums, I would say 95% if not more of that work has been made by assistants you’ll never hear about. Some artists come around and sign their name on a piece, and then it goes out the door while someone else just got no credit and pennies on the dollar for making 95% of it. There’s more to it, of course, and it can be a highly complex relationship, but I don’t think I would ever want to get there.There’s plenty of artists who don’t want their assistants to be artists.

It’s hard enough to be an assistant and an artist. It’s almost like brainwashing. You have to embody their aesthetic and build the same way you think they would build. It’s a very direct process. That said, plenty of artists are the opposite of that and are working to change the practices.

The artist I’ve been working under for the last two and a half years, Naama Tsabar, is excellent. She has a range of works, a big chunk of which are these massive felt pieces. Imagine there’s a piece of paper on a wall and you string threads from one corner to the other. Pull the thread taught, and the paper starts to curl. We take that and scale it up to nine or ten times the size and make it with felt and piano wire instead. We connect those to guitar amplifiers, and turn the whole thing into string instruments. Altering the tightness of the wire changes the pitch as well as the appearance of the sculpture. That’s her main series called Works on Felt. I’ve helped a lot with that project and more, and she’s been a big help with my personal work too. That kind of artist is hard to find.

I like to think of that process as a pre-programmed Ouija board of sorts… It becomes this gesture in the ideomotor phenomenon, which is the idea that your subliminal interactions with something creates the illusion of an outside force.

When I look at your work, there is a certain darkness to it. Is there an intentional connection to angelic/demonic imagery and the spiritual in general?

Yes, I would say so. As I said, the different components of these sculptures have unique functions. Some of the samplers I use, which can be essentially tape-recorders of sorts, have a feature where they use the background electromagnetic noise in the air. It’s the static you hear between radio channels. The sampler uses that as a seed to generate random elements. In doing that it creates this generative chance where if everything lines up at the same time, it’ll record you, and then it will play your sound back to you.

I remember experiencing that feedback at your solo show at Mery Gates in 2021. The gallery was packed for the opening, so the reverberations of everyone’s voices sounded like the ocean. Nothing sounded distinct. It felt real transient, like I was moving through some liminal space or the Gates of Hell.

I like to think of that process as a pre-programmed Ouija board of sorts. It’s a scenario where you, the piece, and the relationship between you, conjure something unique out of the experience. Even though, in the end, what you get out of it is what you put in. It becomes this gesture in the ideomotor phenomenon, which is the idea that your subliminal interactions with something creates the illusion of an outside force.

There’s this great book called Vehicles, Experiments in Synthetic Psychology by Valentino Braitenberg. The author is a roboticist who explores this idea of simplicity in machines and robots that you can build but still project extremely complex behaviors onto. The primary example he starts with is a small robot with a light sensor and a motor. Depending on how you hook it up, you can have the robot run away when you shine a light on it. It’s a simple connection. But when you see that happen, you may project the idea that it is afraid of the light. Or that it likes to hide in darkness. If you reverse the input control and it freezes in light, then you might project onto it that it thinks it’s been seen, and it freezes when noticed.

Any electrical system that’s complex or sophisticated allows you to have that moment of conjuration. It’s mystical in that way.

What are you conjuring next?

I’ve been interested in how to build out more ambient spaces. I’ve started working more with drones, filters, and similar items. But samplers have this beautiful function economy in the way that they will build out a space based on the space itself.

This opening I did at the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art featured a sampler circuit that was on the more sophisticated side. I was listening to it, and when nobody was there at the very beginning, it sounded like just the space. It sounded like people walking through and me standing next to it and walking up to it. But then, during the opening, it reflected the people rushing in. It got louder. And louder. And it, in turn, made the space louder. It was strange, but I like the relationship of a piece learning a space, mimicking a space, but then also having the possibility of incepting something into that space. If you walk over to it and say something, and then later I walk by it when it plays it back, I’m being incepted by something you added. Some people don’t like it. They might just see it as a microphone and speaker.

But I think there’s definitely something to how the form is mirrored in the function. Art can take parts of you and send them back, and maybe it feels like you’re getting something out of it that wasn’t there already. I like that.